This new visual arts section of Malaysia Design Archive is proudly done in collaboration with Ilham Gallery. The first collection features a series of articles from four magazines during the 1950s. The articles cover topics around arts and culture, and presents an interesting insight into the evolution of visual arts and the nation’s history. We are embarking on this project in attempt to enrich the exploration and interrogation into the discourse of visual arts in Malaysia. We are also calling for volunteers who can help us with transliteration of the articles that are originally written Jawi, for the second collection.

__

In Search for an Art Public: An Introduction to 1950s articles on art and culture in Jawi

Simon Soon

Picture-making, or more accurately, image-making (penggambaran) was largely absent from the customary arts in this part of the world from the 14th century with the arrival of Islam. Informed by a religious proscription against representational verisimilitude of living sentient beings, aniconic forms of decorative motifs that became the artistic mainstay instead favoured abstraction and stylisation.

So entrenched was this thinking in Malay Islamic early modern visual culture that when figurative representation gradually appeared in printed media for local consumption in the 19th century, it had to be reconciled with the general Malay populace. This was a gradual process of acculturation that required the local population to regard image-making differently.

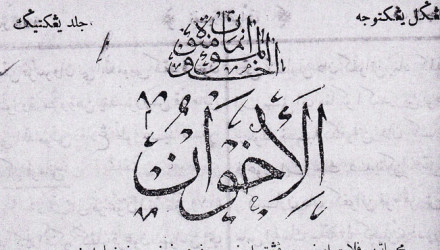

In 1929, an editorial that appeared in the periodical Al-Ikhwan had pleaded with its readers that the benefits of picture-making outweighed customary reservations that pictorial representation automatically constitutes idolatry. Instead, the anonymous writer assessed pictorial representation in terms of its usefulness (sangat-sangat berguna). The central argument was that it could commemorate significant dates (memperingatkan tarikh). Whether these were old or new works, the article drew a connection between picture-making and the notion of human progress (kemajuan manusia).

As debates ensued following the proliferation of Malay presses from 1920’s onwards, the emergence of pictorial representation in Malaysia became entwined with the growth of cultural nationalism. Pictorial forms were directly associated with ideals of enlightenment and modernity. In effect, what is implied here was a belief that pictorial representation brought with it a sense of historical consciousness, which doubly served as an engine for human progress.

The pictorialisation of the human figure was therefore ineluctably linked to a wider desire in the modern project of picturing the nation. This desire was, and still is, a means through which an imagined community could be prospected, to use a phrase coined by Benedict Anderson in his study of print nationalism. The growth of periodicals not only facilitated textual knowledge but circulated alongside textual discourses were also pictorial visions that fostered a growing sense of collective national identity.

This initial compilation of texts owes a great deal to the original research first undertaken by Ahmad Suhaimi in his 2007 publication, Sejarah Kesedaran Visual di Malaya (The History of Visuality in Malaya). In his research, Ahmad Suhaimi underlined the significance of print media in helping forge a new ‘visual awareness’ amongst the Malay public, facilitating the acceptance of illustrative representations of the human figure, which was foreign to its customary visual repertoire.

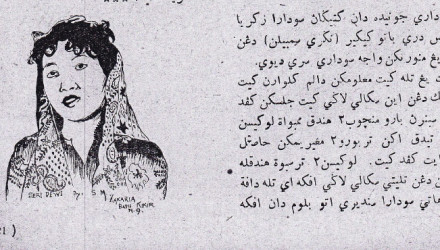

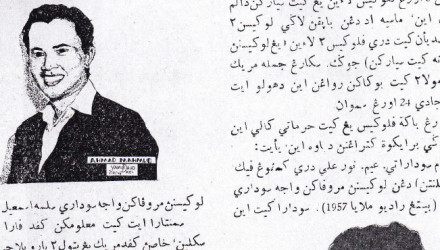

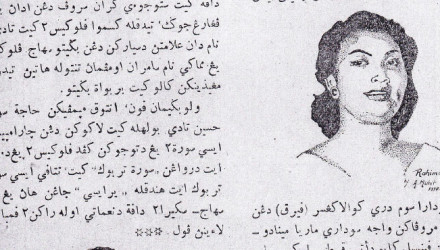

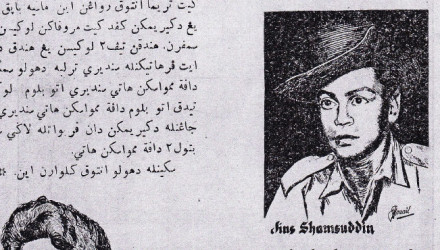

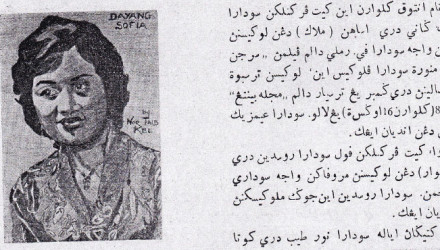

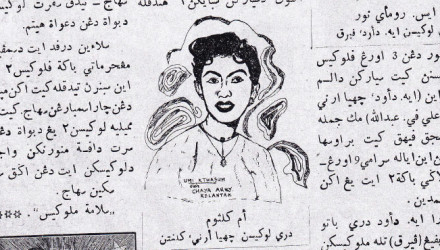

Ahmad Suhaimi’s book was used as a springboard to gather some of these materials that are now shared here. What can a compilation of articles on art and culture found in the pages of 1950s Malay-language magazines aimed at general readership tell us about the intellectual and cultural climate of 1950s amongst Malay reading intelligentsia of that period? On the one hand there was a less rigid cultural distinction between high art and popular entertainment. This does not mean it didn’t exist. Bintang for example had a much more interactive appeal, inviting readers to submit their drawings of celebrities that are then published in its pages. Jin Shamsuddin, P. Ramlee, Saloma and many other Malay showbiz personalities had their portraits drawn by eager fans. In this way, a community can be seen to be taking shape, one that was driven a common popular culture.

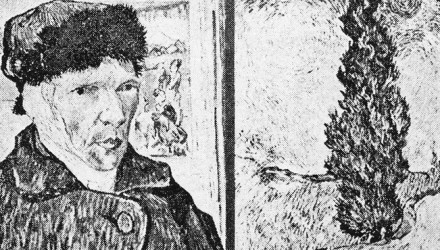

Magazines like Majalah Seni took the initiative to publish more insightful and polemical texts that aimed to inform and educate. These range from discussing the role of art in society to articles that attempted to explain Picasso’s ‘confusing art’ to its readers. Perhaps the most extensive coverage on art and culture in the post-war period amongst the Malay language magazines can be found in Mastika. Mastika prior to the mid-1990s offered very different reading material to its reading public. It was more of a current affairs magazine that covered a wide range of topics.

The articles compiled from these publications can be roughly divided into four categories:

Firstly, there were general surveys of Euro-American art history, often in the form of artist profiles. There were also attempts at explaining to readers what modern art is. Essays looking at more specific issues were also published. For example, a later essay even considered the debates surrounding American abstraction. Secondly, these essays highlighted the important cultural ties between Malay and Indonesian modern art. Not only were Indonesian artists closely profiled, some of these artists were also exhibiting their works in Malaya. Thirdly, there were essays that attempted to define ‘seni lukis kita (our art)’. These were essays that prospected the direction of Malay or Malayan art, as well as its shape, scope and constitution. Finally, there were also articles that addressed the broader question of Malay culture.

These categories demonstrate how a field of ideas and discourses shaped the thinking of Malay-speaking artists and their interest in defining the role of modern art in society to a growing reading public. This cultural field also possessed nationalist ambition and had the broader populace in mind. Just a year before the independence of the Federation of Malaya, the 3rd Malay Language and Literature Congress was held in 1956. Mohd Salehuddin reported on his participation at the Congress, where as part of the proceedings, he also contributed a tentative glossary of Malay translations of art terms. Though the listing was, by and large, technical, he concluded with the question of whether these terms would be simply transliterated or translated and weighed the pros and cons of both approaches without coming to a conclusion. The Congress also hoped for the future translation of art books into the Malay language as well as further research into Malay art and culture.

On the whole, the Congress marked a significant turning point in the politics of the Malay language and culture. It was also at the Congress that Malay language reformers decided on the romanisation of the Malay script. In effect, it was a cultural convocation that signaled a desire to transform the Malay language from a communal tongue belonging specifically to one ethnicity into one that would belong to a multi-cultural nation.

It is hoped that the transliteration of this small selection of articles pertaining to art and culture published in Jawi makes accessible for most of us who do not read Malay in the script and provides some context into a particular period in Malaysian cultural and intellectual history. Needless to say, the project is an on-going one; we will continue to upload more transliteration of Jawi texts over the coming months with the help of volunteers as well as additional historical and critical essays that might help frame some of these materials. The aim is to create a database that will facilitate and encourage future researchers interested in one crucial aspect of Malaysia’s visual cultural history.

** The larger project, which will be shared over time, could not be realised without the generous support provided by Ilham Gallery. Special thanks go to research assistant Hafzan Zannie Hamza, for compiling the texts, as well as, translation studio and publishing house, Teratak Nuromar, for undertaking the transliteration of a selection of these texts. I also like to acknowledge the enthusiastic support from Malaysia Design Archive, who readily agreed to host these texts and share them with the Malaysian public.

*** This introduction essay is largely an amalgamation of two essays prepared for the exhibition Picturing the Nation that was held at Ilham Gallery from August – December 2015. For further reading, see ‘Of Gambar and National Bodies’, Picturing the Nation (Catalogue), Kuala Lumpur: Ilham Gallery, 2015; and ‘Moving Suara for Sovereignty: Reading Shifts in 1950’s Modern Art Discourse in Malay through Kamus Politik’, Dato’ Hoessein Enas: From His Personal Collection, Kuala Lumpur: Ilham Gallery, 2015.

Majalah Bintang

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 88)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 87)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 86)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 85)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 84)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 82)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis Kita (No 80)

Title | Tajuk : Kita Hormati Bakat Pelukis-Pelukis Tanah Air Magazine | Majalah :

Majalah Mastika

Garisan Sejarah Kesenian dan Pertukangan Melayu

Title | Tajuk : Garisan Sejarah Kesenian dan Pertukangan Melayu Magazine | Majalah :

Antara Timur dan Barat

Title | Tajuk : Antara Timur dan Barat Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Melihat dan Menggembari Gambar-Gambar Lukisan

Title | Tajuk : Melihat dan Menggembari Gambar-Gambar Lukisan Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika

Seni Lukis Kita

Title | Tajuk : Kebudayaan : Seni Lukis Kita Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Kebudayaan Melayu

Title | Tajuk : Kebudayaan Melayu (Dari Meja Pengarang) Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika

Kebudayaan

Title | Tajuk : Kebudayaan Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author | Penulis : Madung Lubis

Bahasa Melayu Dalam Lapangan Seni Lukis

Title | Tajuk : Bahasa Melayu Dalam Lapangan Seni Lukis Magazine | Majalah :

Seni Lukis Indonesia

Title | Tajuk : Seni Lukis Indonesia Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author | Penulis : –

Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (5)

Title | Tajuk : Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (5) Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (4)

Title | Tajuk : Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (4) Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (3)

Title | Tajuk : Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (3) Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (2)

Title | Tajuk : Pengertian Tentang Lukisan (2) Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author

Pengertian Tentang Lukisan

Title | Tajuk : Pengertian Tentang Lukisan Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author | Penulis :

Pahlawan Tanahair – Raden Abdullah

Title | Tajuk : Pahlawan Tanahair – Raden Abdullah Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author | Penulis :

Pelukis Melayu Ke England – Essay on Surya bin Mohayani

Title | Tajuk : Pelukis Melayu Ke England – Essay on Surya bin

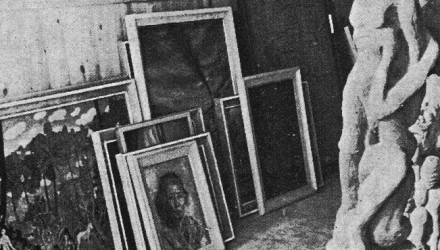

Photo Caption | Tanpa Tajuk

Title | Tajuk : – Magazine | Majalah : Majalah Mastika Author | Penulis : – Date | Tarikh :

Majalah Seni

Bangsa Melayu dengan Kebudayaannya

Title | Tajuk : Bangsa Melayu dengan Kebudayaannya Magazine | Majalah : Bil. 11, Majalah Seni

Kisah-kisah Seni dari Pengalamanku

Title | Tajuk : Kisah-kisah Seni dari Pengalamanku Magazine | Majalah : Bil. 3, Majalah

Jejak Seni Pelukis-Pelukis Kita

Title | Tajuk : Jejak Seni Pelukis-Pelukis Kita Magazine | Majalah : Bil. 6, Majalah

Lukisan Raden Saleh Menipu Barat

Title | Tajuk : Lukisan Raden Saleh Menipu Barat Magazine | Majalah : Bil.

Berbagai Aliran Dalam Seni

Title | Tajuk : Berbagai Aliran Dalam Seni (sambungan yang lalu) Magazine | Majalah : Bil.

Masyarakat dan Seni Lukis

Title | Tajuk : Masyarakat dan Seni Lukis Magazine | Majalah : Bil. 11, Majalah

Al-Ikhwan

Gambar atau Lukisan

Title | Tajuk : Gambar atau Lukisan Magazine | Majalah :

Qalam

Pengaruh Seni Lukis Islām

Title | Tajuk : Pengaruh Seni Lukis Islām Magazine | Majalah : Qalam Column

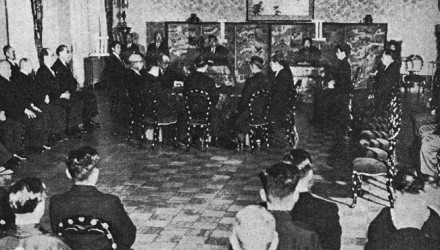

Perempuan dalam Majlis Meshuarat

Title | Tajuk : Perempuan dalam Majlis Meshuarat Magazine |